The Art Beyond the Craft

Having exquisite lotus tea, meticulously scented to perfection, is only half the journey. The brewing itself is an equally refined art—one that separates the mere drinker from the true devotee.

The people of ancient Hanoi do not merely drink tea—they contemplate it. They savor the fragrance, the flavor, the distilled essence of heaven and earth crystallized in each cup. This is not sustenance but communion, not thirst-quenching but soul-feeding. For all ceremonial occasions and when receiving honored guests, the first choice of Hanoi families remains lotus tea, especially the legendary brew from Quảng An, West Lake.

For Hanoi people, tea contemplation is a supremely elaborate and refined art. When the tea in question is lotus tea—once reserved exclusively for noble courts—the art becomes even more exacting. Sometimes we possess excellent lotus tea but lack the knowledge to brew it properly, and thus we cannot create a cup worthy of its value. Therefore, the ancient Hanoi masters approached lotus tea brewing with both meticulous care and artistic sensibility.

Lord Trịnh Sâm, one of Vietnam’s most celebrated feudal rulers, was renowned as both a tea lover and tea connoisseur. History records that during summer in the imperial capital of Thăng Long, whenever he desired to contemplate lotus tea, he would dispatch his servants to West Lake. They would row out to the lotus fields and painstakingly gather dewdrops from lotus leaves, collecting these pearls of morning moisture to brew his tea.

Water Source for Tea Brewing

The four fundamental principles for an exceptional cup follow the ancient maxim: “first water, second tea, third brewing, fourth teapot“

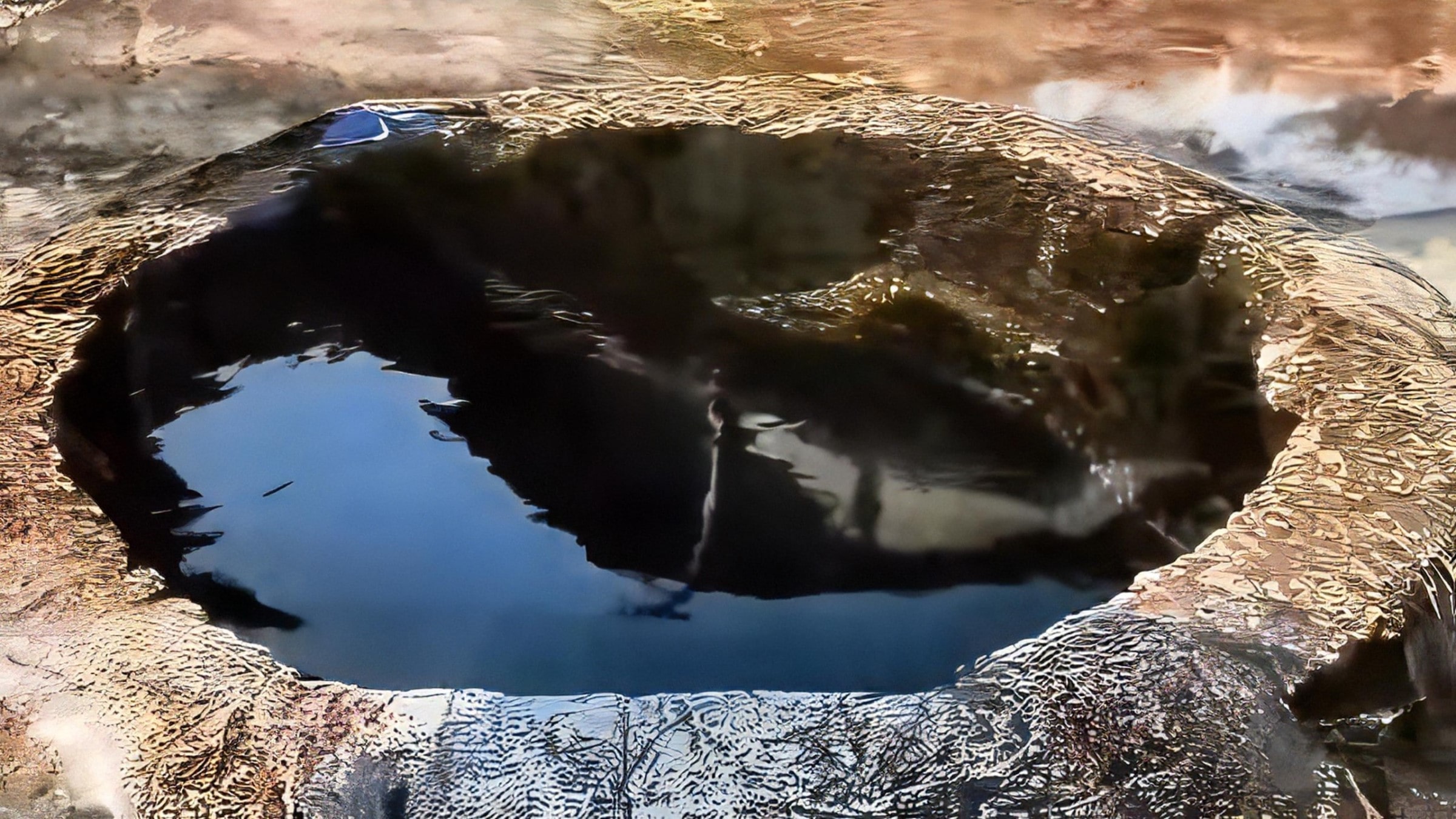

When we already possess a supreme tea like West Lake Lotus Tea, our next concern must be the water source. The elders often said “mountain stream water for mountain tea,” and they summarized this wisdom in a famous saying: “mountain streams is best, river water is all right, well-water ranks third.“

Mountain water is best means spring water from the source brews the finest tea. Therefore, if you can obtain water from headwater streams where the flow runs gentle and harmonious, this is your premier choice. However, avoid collecting water from areas of rapid falls and cascades where the current runs violent—such water brews tea quickly but disperses the fragrance too soon. Likewise, never take water from stagnant pools, as this brews slowly and fails to awaken the tea’s aromatic soul.

River water is all right refers to water drawn from the middle of rivers, far from human habitation—the second finest choice. Well water ranks third means mountain well water ranks third in excellence.

Beyond these three sources, the ancients often used rain water for tea brewing. However, they never collected water from the season’s first rains, waiting instead for the third or fourth rainfall before gathering water in earthenware vessels. The reason was that the first seasonal rains wash dirt and debris from the air and rooftops, carrying impurities that would taint the tea.

These were the primary water sources that ancient tea masters favored. However, in our modern era of environmental pollution, where many rivers and streams have become contaminated, we can instead use purified water—such as RO-filtered water with a near-neutral pH (around 7) and low mineral content, or commercial brands like Aquafina and Dasani—for brewing. Absolutely avoid tap water containing chlorine, as chlorine destroys all tea fragrance and flavor.

Choosing Right Teapot

After securing excellent tea and good water, the tea service becomes crucial. For those who brew lotus tea, you must always dedicate a specific pot exclusively to lotus tea. Never brew other teas in this vessel, lest foreign flavors contaminate the pure lotus essence.

When selecting a brewing pot, simplicity surpasses ornamentation. A simple earthenware pot with harmonious round proportions, free from ostentatious styling, becomes the intimate companion that elevates fragrance and preserves flavor for each tea leaf. The pot’s size should also match the number of guests, ensuring the right balance between elegance and practicality.

Place your hand on the pot’s body and interior—the texture should feel smooth as a baby’s skin, without roughness or coarseness.

Tap the lid gently against the pot’s rim and listen to the sound—it should ring clear and crisp as temple bells in the morning air, indicating fine clay and masterful firing.

Set the pot upside down on the table—the handle, spout, and rim must align in perfect straightness. If the spout sits too low, tea will overflow before fully steeping; if too high, the flow becomes clumsy, disrupting the elegant grace of tea contemplation.

The lid must fit precisely, snugly sealed. When closed, it should produce a definitive “click,” like an iron promise between person and tea. Finally, test-pour water—cover the air hole on the lid with your finger; if the water stops flowing completely, you have found an airtight pot, perfect as a masterwork of artisan refinement.

Each small detail represents not merely technique, but a mirror reflecting both the craftsman’s skill and the quality of the clay itself.

From Leaf to Liquid

When brewing and contemplating tea, the ancient people of Hanoi always moved with tranquil grace—unhurried, relaxed, deliberate, serene, and naturally at ease.

The first brewing always contains the most essential treasures. So how do we create the most exquisite cup to offer our honored guests?

First, pour boiling water inside the pot to warm it while simultaneously cleansing the interior. Then replace the lid and gently shake so the boiling water can rinse the entire inner surface evenly. Next, set the pot down and pour boiling water over the lid to warm the entire outer surface. Finally, empty all water from the pot to prepare for brewing.

Add the tea while the pot is still hot. We add just the right amount of lotus tea to the pot, depending on individual taste and pot size. We should neither brew too strong nor too weak—overly strong tea creates overwhelming fragrance and reddish color, while overly weak tea lacks sufficient aroma and flavor for proper appreciation. This is why the ancients called tea brewing “the art of perfect balance.” After adding the tea, pour in hot water to fill about half the pot. Gently swirl and immediately pour the water out—this quick rinse awakens the tea without allowing its delicate aroma to escape.

After the tea has been awakened, pour fully boiled water until it just overflows, then stop.

Water temperature depends on individual preference. Use 212°F (100°C) boiling water for strong-flavored tea; however, for optimal flavor, use boiled water cooled to around 175–185°F (80–85°C), which brings out the tea’s fragrance while keeping the taste smooth and less astringent.

We always let boiling water overflow the pot lid—first to carry away any dust particles, second so when we replace the lid, the water creates a tight seal, forming a water gasket around the lid that keeps heat perfectly contained. Next, we pour water over the lid and outer surface to “bathe the pot,” keeping it evenly heated inside and out while making it gleam.

When we add boiling water to the tea pot, we always wait about 1 to 2 minutes for the tea to properly steep. While waiting, we place all serving cups in a tea basin and pour boiling water over them—both for cleanliness and to heat the cups. One of the first standards for excellent Vietnamese tea is that the cup must be warm in your hands.

After cleaning and heating the cups while the tea steeps, we lift out the cups and pour tea from the pot into the serving pitcher, then from the pitcher into individual cups. This ensures all cups have perfectly even flavor—none too strong, none too weak.

The common mistake—steeping tea leaves in the pot while drinking, pouring cup after cup without using a serving pitcher—creates an overwhelming concentration that drowns the delicate lotus essence in bitter strength. The proper way demands that when you lift the teacup, only the gentle whisper of lotus fragrance should dance across your senses, light as morning mist.

Immediately after pouring the first water into the serving pitcher, don’t rush to discard the tea leaves—that would be truly regrettable. The leaves still hold countless layers of fragrance and flavor waiting to be revealed. Pour more boiling water into the pot, leisurely steep the second round, then continue this process. Through this method, we can enjoy multiple steepings, unlocking the complete essence treasured within each leaf.

Depending on the tea grade, some yield only three or four steepings; others are so precious they can be steeped six or eight times before releasing their final whisper of fragrance. To ensure each steeping maintains consistent aroma and color, preventing later waters from becoming too weak compared to the first, here’s a small secret: between adding fresh water, don’t pour out every drop of old tea from the pot into the serving pitcher. Leave a little so the flavor continues seamlessly, deepening and harmonizing through each steeping.

Mindful in Every Cup

When contemplating lotus tea, the ancient Hanoi people always chose pure, natural spaces—places with flowing water sounds, miniature mountains, flowering plants, and birdsong. This pristine environment calms the mind, and only with a calm mind can we fully appreciate the exquisite fragrance and flavor of lotus tea.

When enjoying lotus tea, Hanoi people always focus their complete attention on the present moment, seeking to perceive each nuance of fragrance, each note of sweetness in the tea.

After lifting the cup and taking a deep breath to appreciate the tea’s aroma, we then bring the cup to our lips and sip gently, holding the tea in our mouth for about five to seven seconds to fully taste it before slowly swallowing. Hanoi people contemplating lotus tea never gulp it down but always savor each small, gentle sip to experience the complete aromatic and flavorful journey of each cup.

In ancient times, anyone who drank tea too quickly would be scolded by elders as a “buffalo drinker,” inspiring this mocking verse:

Vai u thịt bắp mồ hôi dầu

Lông nách một nạm trà tàu một hơi

Literal Translation: “With hunched shoulders and muscles gleaming with oily sweat,

Armpit hair in clumps, downing tea in one breath.”

Presenting tea also represents cultural refinement, noble character, and intimate understanding between souls. When offering cups of fragrant lotus tea to honored guests, Hanoi people always present tea with both hands accompanied by a warm smile, following the famous verse by the 11th-century Lý Dynasty Zen master Viên Chiếu:

Tặng quân thiên lý viễn

tiếu bảo nhất âu trà

tặng người ngàn dặm cách xa

cười dâng chỉ một chén trà thế thôi

Literal Translation: “To one a thousand miles away I offer

With laughter, just this single cup of tea—

Nothing more than one small vessel,

Yet it carries all my heart’s sincerity.”

The tea cup offered with both hands and a bright smile symbolizes a precious gem resting on a lotus blossom, presented with the desire to bring the most peaceful energy and beautiful blessings to honored guests. Simultaneously, the image of two hands lifting the tea cup carries gratitude toward the farmers and artisans who labored through sun and dew to create this exquisite cup of tea.

When contemplating tea, we gaze deeply into the cup, breathing in the gentle fragrance, and discover that the cup contains not just tea and water—we also see sunshine, air, earth, raindrops, and the sweat that nourished the tea plants and lotus to grow. We realize the Buddhist truth of non-self: no entity exists independently; all things interconnect and depend upon each other for existence. This cup of tea could not exist in this present moment without sunshine, earth, or the rain that watered the plants.

No beverage teaches humanity as much as tea. Tea teaches us to maintain cleanliness and order in every small detail. Tea develops our patience through each brewing step. Tea reminds us to live with humility, gentleness, and simplicity. Above all, tea helps us calm our minds, examine ourselves, and from there cultivate and perfect ourselves each day.

For Vietnamese people, drinking tea is not merely culture, not merely art—it is also a method for cultivating the mind and character, nourishing our hearts toward peace. When our hearts achieve peace, we attain true happiness.

Through the sacred ritual of brewing, we have completed our pilgrimage into the soul of West Lake Lotus Tea—from its thousand-year heritage to the devoted hands that craft it, and finally to the contemplative ceremony that reveals its celestial essence. IIf you haven’t read [Part I: The Sacred History] and [Part II: The Art of Handcrafted Lotus Scenting], discover them to fully appreciate the profound devotion in every cup.

If you wish to experience a tea shaped by everything you have just read — where fragrance is not added, but patiently transferred — we invite you to explore our current West Lake Lotus Tea collection. Each batch is crafted in limited quantities.

→ Experience West Lake Lotus Tea — View the Collection